Screen: sm

Bringing a Lake Back to Life

A Roadmap for Restoring Urban Lakes

Introduction

This is a story of Venkateshpura Lake – a neighbourhood lake tucked away in the northern part of Bengaluru. As the city grew around it, the lake gradually lost its ecological health, eventually slipping into stagnation and decline. Until a group of concerned citizens chose to bring it back to life – not only for the lake’s future, but for their own well-being. Their story of collective action offers important signposts for any community seeking to rejuvenate a lake.

Place

Where is Venkateshpura Lake?

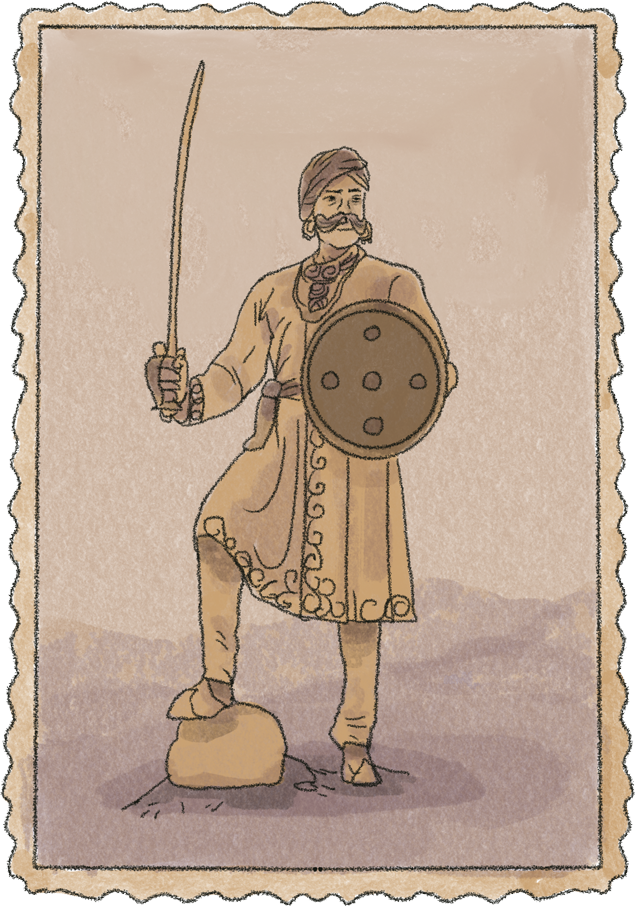

Venkateshpura Lake is a relatively small lake, covering just over 10 acres. It is managed by the Greater Bengaluru Authority (GBA), Bengaluru’s civic body. Located in Sampigehalli, Arkavathy Layout, Jakkur Ward, the lake is known locally as Sampigehalli Lake, its old name.

Venkateshpura Lake is a relatively small lake, covering just over 10 acres. It is managed by the Greater Bengaluru Authority (GBA), Bengaluru’s civic body. Located in Sampigehalli, Arkavathy Layout, Jakkur Ward, the lake is known locally as Sampigehalli Lake, its old name. Once standing amid open farmland, the lake area provided pasture and water for livestock. As Bengaluru expanded outward, these fields gave way to residential complexes and public utility buildings, transforming a pastoral landscape into a dense urban setting.

Once standing amid open farmland, the lake area provided pasture and water for livestock. As Bengaluru expanded outward, these fields gave way to residential complexes and public utility buildings, transforming a pastoral landscape into a dense urban setting. There is a ruggedness to the lake’s identity that comes from the rocky outgrowth both within it and along its periphery. One of its rocky projections bears the nineteenth-century Sampigehalli Auxiliary Tower Station – a site with a subcontinental story to tell. Adjacent to the waterbody is the Jarabandemma Temple, built on an imposing rock, which holds unique significance due to the distinct rituals observed even to this day.

There is a ruggedness to the lake’s identity that comes from the rocky outgrowth both within it and along its periphery. One of its rocky projections bears the nineteenth-century Sampigehalli Auxiliary Tower Station – a site with a subcontinental story to tell. Adjacent to the waterbody is the Jarabandemma Temple, built on an imposing rock, which holds unique significance due to the distinct rituals observed even to this day.

History

“Keregalam Kattu, Maragalam Nedu” – “Build lakes, plant trees” – is a Kannada saying attributed to the mother of Kempe Gowda, the governor under the Vijayanagara Empire, famed for founding the Bengaluru city in the 1530s. Kempe Gowda is remembered today for creating nearly a hundred lakes and lining the city’s roads with trees, thereby shaping the city’s identity as the ‘City of Lakes’. Over the years, many lakes have been lost, but a few, like Venkateshpura Lake, now stand as a renewed source of hope amid rapid urbanisation.

Tower station

Built in 1803, the Sampigehalli Auxiliary Tower Station (SATS) overlooking Venkateshpura Lake witnessed the Great Trigonometrical Survey (GTS) of India, one of history’s most ambitious scientific projects. Beginning in 1802, the GTS used triangulation to map the Indian subcontinent and even revealed Mt Everest as the world’s tallest peak. Its architect, Col. Lambton, began a pilot survey in the city, establishing auxiliary stations, like SATS, as key observation points to reduce errors. They became one of the many principal triangulation stations. Once marked by a twelve-foot pillar, the GTS tower now retains only the deep circular pit where it stood.

Jarabandemma temple

The Jarabandemma temple, perched on a rocky outcrop by the lake, is a historic sacred site believed to date back to the era of the Mysore kings. As per local tradition, it was a resting place for soldiers on the move. During Shravan, the fifth month in the Hindu lunar calendar, villagers gathered here to pray for rain and offered ambali, a millet-based dish. A spring from a natural cleft in the rock near the entrance is seen as a miraculous gift. Inside the temple, uncarved stones represent powerful protectors – Jarabandemma, Akkayamma and the Saptamatheyaru – central to the community.

Hydrology of the lake

The lakes in Bengaluru were constructed to harvest rainwater along the streams, and they flowed across an undulating terrain, connected by rajakaluves or stormwater drains. This network of lakes formed a seamless cascading system from a higher to lower elevation along three main valleys of the city – Hebbal-Nagawara, Koramangala-Challaghatta and Vrishabhavathi.

Venkateshpura Lake lies within the Hebbal-Nagawara Valley and has an independent catchment area that leads to the valley. It is at the apex of a series of lakes.

Of the 72 lakes in this valley, only 32 still have adequate physical structures to allow water to flow. In many of these lakes, the inlets, outlets and stormwater drains that did exist were either broken or encroached upon by built structures or diverted to prevent raw sewage from flowing into these lakes.

Venkateshpura Lake receives water from stormwater drains and a few other inlets. Its outlet meets the outflow of Jakkur Lake, after which the combined flow drains downstream into Rachenahalli Lake.

Degradation of the lake

1 / 10

As the modern city slowly encroached, the lake lost its natural connection with its downstream lake. Water hyacinth took over large parts of the waterbody. Invasive plants like lantana and parthenium spread around the lake crippling its ecological balance. Large-scale mining around the lake wrecked the natural rock formation. Quarrying destroyed parts of the historical GTS structure. Untreated sewage was released into the lake from neighbouring buildings. The water turned stagnant and green with algal bloom, killing fish and other aquatic life. Plastic, cloth waste and construction debris added to the deterioration of the lake.

Key actors

Civilisations evolved around waterbodies. Be it a pond or a lake, a waterbody is a shared resource. For its communities, it sustains livelihoods, shapes cultural practices and supports ecological balance.

Biodiversity

Venkateshpura Lake – stagnant and overrun by invasives and waste – still supported life. Grey-headed swamphens, Eurasian coots and black-winged stilts went about their business as usual, while a few cormorants lingered. Introduced fish survived, though native ones had vanished. Rock agamas basked, geckos slipped through crevices, butterflies flitted and keelbacks rippled the water. The lake’s flora was dominated by invasives.

Fisherfolk

The lake, a traditional fishing ground, is periodically leased by the municipal body to local fisherfolk. The current leaseholder had stocked the lake with commercial fish, such as rohu and catla. But the dense algal bloom and pollution rendered even these resilient fish vulnerable. As the lake’s health declined, so too did the fragile livelihood of the fisherfolk.

Residents

For residents, the small lake, with its green grass, trees and rocky outcrops, was an oasis amid the bustling city. The rocks held traces of history. Though never really maintained, the lake kept the neighbourhood cool and fresh. Gradually, however, development choked its inlets and outlets, transforming the wetland into a wasteland.

Researchers

Researchers emerged as key allies when residents sought support to save the lake. They contributed scientific expertise to restore its fading health, helping strengthen and accelerate the community’s vision for the lake.

Government

Venkateshpura Lake came under the management of the Greater Bengaluru Authority in 2016. It faced several challenges, like encroachments, quarrying, illegal dumping and algal bloom. Local conservation efforts to restore it, however, generated sufficient data and momentum to prompt government action. Krishna Byre Gowda, the local MLA and now the State Revenue Minister, publicly endorsed the restoration initiative. This move was crucial in galvanising all-round support for the lake’s revival.

Pastoralists

The grassland flanking the lake had been the grazing grounds for cattle, sheep and goats, known locally as gomala. It was among the last remaining patches in the neighbourhood with easy access to grass and water. Pastoralists who grazed their livestock here earned their livelihood by supplying milk in the surrounding areas.

Migrants

Migrant workers living nearby, who otherwise had to scout around for water to wash their clothes and vessels, could access the open, unfenced lake. Their children were always up for a quick dip, especially with plenty of rocks serving as diving boards.

Joining hands

It was clear that people living around Venkateshpura Lake were united in their desire to save it. But meaningful restoration requires a shared vision, which means ensuring that all voices – local communities, government institutions, researchers and other local actors – come together and align their needs with a shared vision for the future.

Researchers led multiple biodiversity walks like bird, butterfly, bat, ant and bee trails that helped residents appreciate the abundance of life in and around the lake.

Volunteering activities, film screenings and festive gatherings around the lake brought the diverse groups together and helped them understand and appreciate the varied needs of each actor and chart a common vision for the lake.

The community understood the watershed’s role in sustaining the lake and opposed any diversion of catchment land for infrastructure. They pursued the issue rigorously, including filing PILs, to protect the lake and its watershed.

Goals

- Control sewage flow and waste dumping.

- Ensure water from Venkateshpura Lake drains into Rachenahalli Lake.

- Install tech-integrated nature-based solutions, such as floating islands for nutrient retention and aerators for oxygenation.

- Conduct regular water quality monitoring with community.

- Re-introduce native fish and other aquatic species.

- Prepare a systematic plan to assess and quantify the lake’s flora and fauna.

- Implement targeted interventions to restore ecological balance.

- Rebuild food webs and create conditions that enable the return of bird species that once thronged the lake.

- Remove water hyacinth, lantana and other invasive weeds.

- Create natural, unpaved walking paths.

- Plant native species suitable for the landscape.

- Install bee hotels to support pollinator diversity.

- Grow food plants for solitary bees.

- Create butterfly garden patches.

- Showcase the heritage significance of the structure.

- Halt rock quarrying.

- Be vigilant to further encroachments.

- Conduct community activities to inculcate a sense of ownership of the lake.

- Create awareness about using treatment plants efficiently and reusing treated water for secondary purposes within the buildings.

- Organise focused activities for neighbouring school children to familiarise them with the different taxa through nature walks and trails.

- Install informative signage to facilitate meaningful interaction with the lake.

- Form a lake-support group to connect local residents and coordinate activities.

Choosing our mascot- The Pied kingfisher

Unlock Me 🔓

The pied kingfisher, a striking black-and-white bird, seeks clear lakes and rivers, diving effortlessly in pursuit of fish and other aquatic prey. However, as pollution clouded the waters and stagnant conditions prevailed, the kingfisher, which was once seen here, disappeared. It became the natural choice as the indicator species for a healthy lake.

Restoration

Venkateshpura Lake presented several challenges, and addressing them needed to be done step by step.

1. Identifying key issues

2. Lake health check-up

3. Biodiversity survey: A peek

4. Lake clean-up

5. Installing tech-integrated nature-based solutions

6. Rewilding the lake

7. Formation of lake trust

8. Engaging youth through schools

9. Participatory water quality monitoring

Identifying key issues

- Declined water quality with untreated sewage inflow.

- Overgrowth of invasives, such as lantana and parthenium.

- Loss of ecosystem services, like groundwater recharge and biodiversity support.

- Haven for illegal activities.

- Inconducive for human use and recreation.

- Need to involve the local community.

Lake health check-up

- Secchi depth: A method of noting how clear the lake water is, using a disc attached to a rope.

- Dissolved oxygen: A handheld probe with a metre and a sensor measures the amount of dissolved oxygen available for aquatic life – plants, fish and other organisms.

- Shoreline vegetation: Carefully planned and planted shoreline vegetation filters run-off, absorbs excess nutrients and provides shelter for small fish and zooplankton.

Biodiversity survey: A peek

- Butterfly: A total of 31 species were recorded, with Lycaenidae and Nymphalidae families exhibiting the maximum species richness and abundance. Among the most frequently observed were the common cerulean and common four-ring.

- Fish: Six species from two orders – Cypriniformes and Perciformes – were documented through samples from local fishers’ nets and dip nets. Exotic species included Oreochromis niloticus and Cyprinus carpio. Several dead fish were observed, particularly Labeo sp. The lake was nearly bereft of native species.

- Reptiles: Visual encounter surveys conducted during both day and night identified 14 species, including geckos and lizards associated with rocky habitats.

- Amphibians: Night-time audio-visual encounter surveys recorded five anuran species. Notably, frogs with restricted distribution across Bengaluru, such as the common pond frog, were found at the lake.

- Birds: A total of 93 bird species were recorded, including black-headed ibis, red-wattled lapwing, alexandrine parakeet, Indian paradise flycatcher and bronze-winged jacana.

- Bees: Invertebrate sampling yielded 373 insect specimens, among which were 18 individual bees from four species. The most abundant insect order was Diptera, which included flies.

- Macroinvertebrates: A total of 2,824 aquatic macroinvertebrate individuals were collected post-monsoon. They belonged to 26 families, of which 96% were predators.

- Plants: By the time the baseline survey commenced, aquatic and emergent vegetation had been cleared as part of the ongoing lake management. Grasses and herbaceous plants occupied the bunds. Invasive species, such as parthenium and lantana, were prevalent throughout. Pongamia pinnata was the most common tree species.

Lake clean-up

- Removal of water hyacinth, plastic and other accumulated waste.

- Uprooting of lantana and parthenium from the area surrounding the lake.

- Collecting quarry and construction waste to be repurposed.

Installing tech-integrated nature-based solutions

- Aerators, by circulating water, increase dissolved oxygen levels.

- Floating islands, with native vegetation like Centella asiatica and Typha angustifolia, filter contaminants and prevent nutrient build-up.

- Removing water hyacinth and other weeds along the shore and planting native species facilitate soil stability and support biodiversity.

Rewilding the lake

- Butterfly mounds layered with stones, logs, soil and compost to grow host plants for caterpillars and nectar plants for adult butterflies.

- A “bee resort” made of natural materials like dead wood, bamboo and twigs, to attract solitary bees that thrive in cityscapes and are vital for pollination, but increasingly lack nesting and foraging spaces.

- Unpaved walking trails instead of conventional cemented paths to encourage slower, mindful walking.

- Trails that mimic dry Deccan gardens, with the grasses Bengaluru historically had.

Formation of lake trust

- Pressure from residents prompts the civic body to take action to restore the lake.

- When restoration efforts lag, residents shift focus to the heritage value of the lake, citing the GTS tower through rallies and collective actions.

- Residents form a trust – Chokkanahalli Sampigehalli Abhivriddhi Forum – attracting significant media attention.

Engaging youth through schools

- Games, biodiversity walks and other activities introduce schoolchildren to the concept of a wetland and its importance, as well as the diversity of flora and fauna present at the lake.

- Schoolchildren engage in a game of metaphors to understand the importance of the lake.

- Students learn to keep a nature journal and record their observations of the wildlife around the lake.

Participatory water quality monitoring

- Residents take part in step-by-step restoration activities, including water quality monitoring.

- Infomercials and water-quality monitoring kits equip them to conduct systematic water-quality checks.

- Equipped with the right skills, residents take ownership of the lake’s responsibilities.

Transformation

After

Before

Improved quality of water

- Water tests show higher dissolved oxygen levels.

- Invasive water hyacinth disappears.

- Native aquatic plants recover.

- The water surface becomes clear and weed-free.

- Algal blooms reduce.

Walking pathways along the lake

- Uncemented pathways allow visitors to connect with the landscape.

- Repurposed construction material and quarry waste serve as canvases showcasing the lake’s biodiversity.

- Artworks, retaining the natural texture of the rocks, help visitors anticipate what they might encounter at the lake.

- Repurposed tyres, debris and lantana serve as seats.

Introduction of native species

- The local fisherfolk reintroduce native fish species.

- Native plant species, such as butterfly bush (Buddleja indica) and peacock flower (Caesalpinia pulcherrima), prioritised for all planting efforts, thrive under people’s care.

- Orchids planted on trees flourish.

Pollinators thrive

- Carefully curated butterfly host and nectar plants, along with bee-friendly species, welcome diverse wildlife visitors.

- Solitary bees settle into the bee hotels.

- A walk along bee hotels helps foster ‘beephilia’ – a fearless appreciation of these important pollinators.

Biodiversity improves

- Bird species, like cormorants, oriental darters, black-winged stilts, ducks and even pelicans, throng to the lake in healthy numbers.

- The floating islands turn into nesting grounds for resident waterbirds.

- The defining moment occurs when the pied kingfisher returns, realising that the water is clear enough for it to dive and hunt.

Educational material

- Researchers developed a pocket guide to the birds and butterflies of Venkateshpura.

- A place-based educational kit, designed for youth engagement, outlines a range of topics, including the water cycle, lake health monitoring tips, methods for sampling flora and fauna, and the lake's ecosystem services.

Community-led conservation

- Sustained community-driven efforts transform the lake from a neglected waterbody into a vibrant public space.

- The lake attracts considerable daily footfall from the community. Even at noon, women can be seen sitting on the benches, enjoying the afternoon breeze.

- The lake forum is well-informed about potential pollution sources and knows whom to alert when issues arise, such as algal blooms.

- Members regularly document and share photos of birds, sunrises and sunsets, building pride and a sense of connection.

- Through the lake trust, residents take charge of the emerging challenges.

- The stage is set for a long-term, community-driven model of lake restoration.

TimeLine

Venkateshpura Nagar Lake Story (2005 to 2025)

2005-2010

A Quiet Landscape

- Sampigehalli Lake, clean and clear, supports small-scale farming and dairy at Sampigehalli village

- Renamed Venkateshpura Lake as the village officially becomes Venkateshpura

- Civic body plants native trees, erects partial fencing with community cooperation

- Civic body gradually withdraws lake engagement

2010-2014

Urbanisation and crisis

- Built-up areas expand around the lake; sewage begins to drain in

- Residents repeatedly appeal to the elected local leader and civic body

- People file PILs; trace lake boundaries and buffer zones

- Residents procure official maps for watershed conservation

2014-2020

Growing pressures

- Apartments rise around the lake; sewage inflow intensifies

- Water hyacinth spreads; weeds overtake the bunds

- Cycle rally organised to save the lake

- Apartment associations join the movement

2020-2022

COVID neglect and a turning point

- Lake chokes under hyacinth during COVID

- Government body denotifies lake buffer for private buildings

- Community mobilisation intensifies

- Media takes note; residents again appeal to elected bodies

2022

Scientific restoration begins

- Civic body recruits an infra company to implement design and part of the DPR

- NGO ATREE joins hands, provides scientific inputs

- ALCON Laboratories prepares detailed project report (DPR)

- Restoration framework co-created with community

- PLUS, a partner, develops expanded DPR

- VIMOS supports implementation of select design elements along with BBMP plans, draining, and dredging

2022-2025

Ecological and social restoration

- Biodiversity surveys conducted

- Water monitored continuously

- Lantana removal initiated

- Butterfly trails established

Rebuilding ecosystem

2022 -2025

- Signages installed about GTS Tower and Temple

- Stakeholder meetings organised

- Nature education module developed

- Day and night walks conducted for community

Community engagement and education

2022 -2025

- PLUS develops zoning and visualisation plans

- Tech-integrated nature-based solutions identified

- Plans roll for floating islands and aerators

- VIMOS helps implement key design elements

Design and innovation

2022 -2025

- Lantana and tyres repurposed into seating

- Construction rubble used for biodiversity art

- Bee resort installed

- Pied kingfisher declared lake mascot

Sustainable initiatives

2022 -2025

- Grazing access maintained for villagers

- Edible grasses and summer water trough established

- Fishermen engaged in restoration process

- Native fishes reintroduced alongside commercial species

Inclusive changes

2023-2025

A thriving common

- Rock-based microhabitats created for reptiles

- Lake receives nearly seventy visitors daily

- Slow walk trails planned

- Visitor observation dashboard developed

A New Beginning

- The pied kingfisher has returned to Venkateshpura Lake. Watching it hover on the lake before diving down to fish gives us hope. The water looks clearer, and the water quality metrics show improvement. Residential areas around the lake haven't ordered a water tanker since the restoration – evidence that the lake is performing its role as an aquifer.

- Walkers, old and young, and enthusiastic birders are regulars at the lake. It has become a safe place for women to sit after work on a hot afternoon.

- Following restoration, biodiversity assessments showed a slight decline in some species. But these were short-term responses to habitat reformation. The system soon stabilised.

However, the work is far from over.

- Water quality must remain consistent, especially in the summer months when the lake recedes, and dissolved oxygen levels can drop to alarming levels. The floating islands and the new plants demand regular care.

- Sustained efforts over the years to retain water in Venkateshpura Lake have helped ensure year-round water storage, supporting groundwater recharge and local ecology. However, these changes have also altered the lake’s natural flow, reducing circulation and occasionally leading to stagnant conditions and algal blooms. As the catchment urbanised, such shifts were inevitable.

- Improving the inlets with nature-based solutions, such as vegetated bends that slow the flow and absorb nutrients before the water enters the lake, is a good way to support the lake’s long-term health.

- While the lake has been restored, the fencing around it, intended to address safety concerns, has unfortunately resulted in limited access for some of the key actors, particularly migrants and pastoralists.

- Preventing illegal drainage into the lake and protecting the fragile historical GTS structure calls for constant vigilance.

Resources

14 resources found

Contributors

Storymap team

Website Developer

Illustrations

Content and Edits

Special thanks to

Gallery

© 2026 ATREE Communications